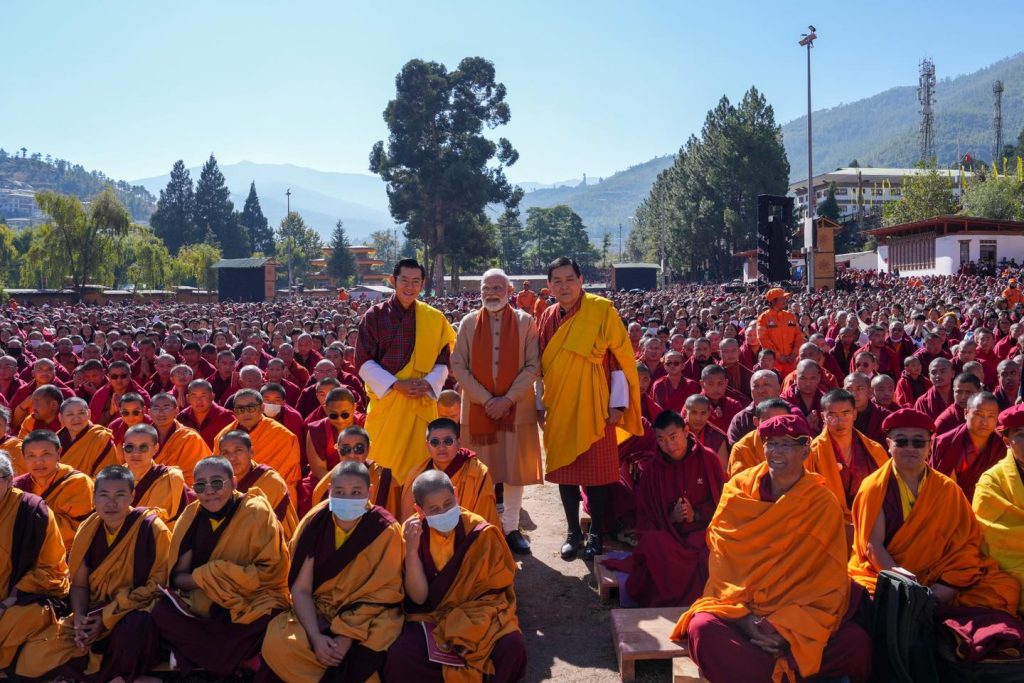

November 11, 2025 – On this auspicious day, I am deeply happy that we are all gathered here at Changlingmethang to pay tribute to His Majesty the Fourth Druk Gyalpo Jigme Singye Wangchuck, to express our everlasting gratitude, and to pray for His Majesty’s eternal wellbeing on His Majesty’s 70th Birth Anniversary.

We owe an enormous debt of gratitude to His Majesty the Third Druk Gyalpo Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, and Her Majesty Yum Kesang Choeden Wangchuck, for giving Bhutan our King of Destiny, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck. His Majesty is a blessing bestowed upon us, the people of Bhutan, by our protective deities.

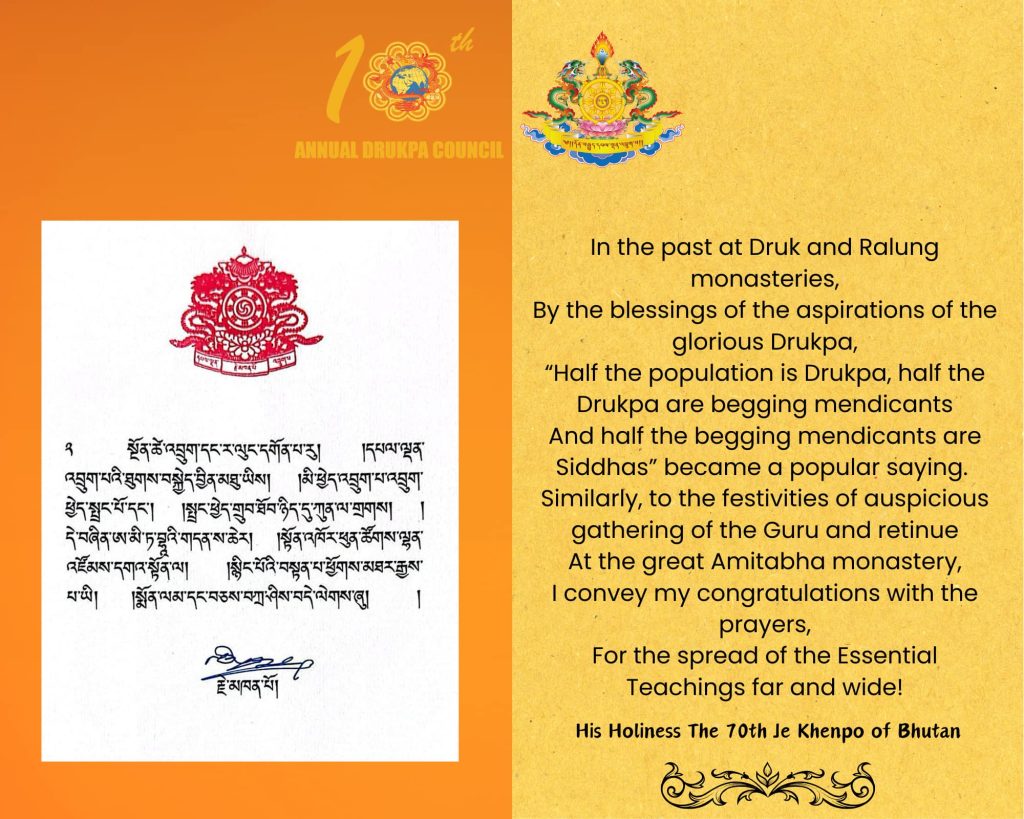

I thank the religious order, led by the Je Khenpo, for their prayers for the Kingdom, and the government and people of Bhutan, for having served His Majesty during his reign with the utmost loyalty and devotion.

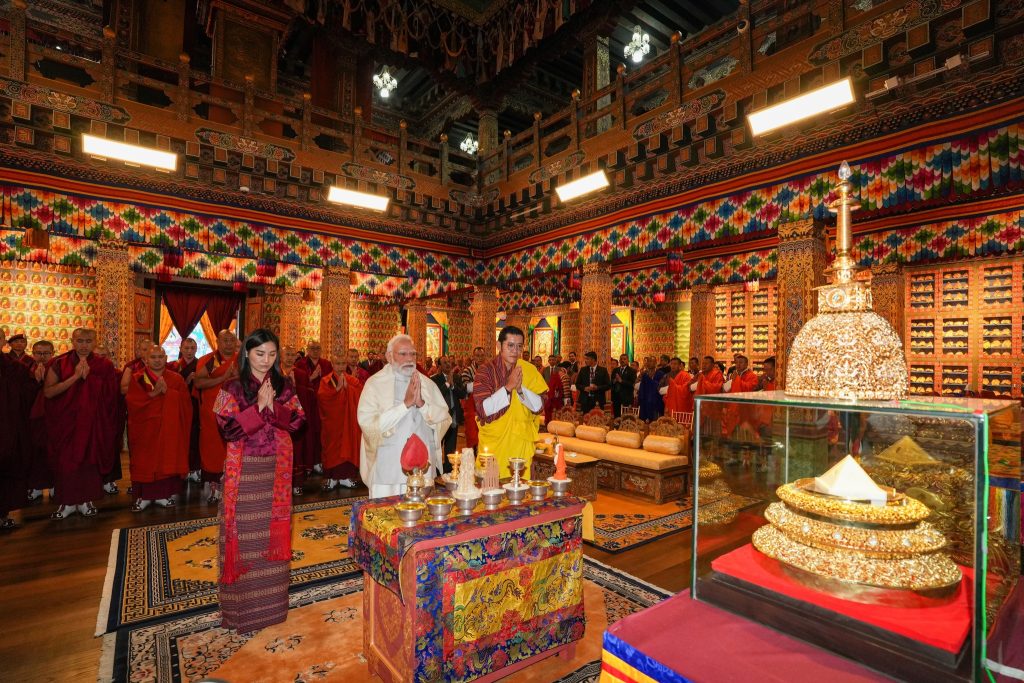

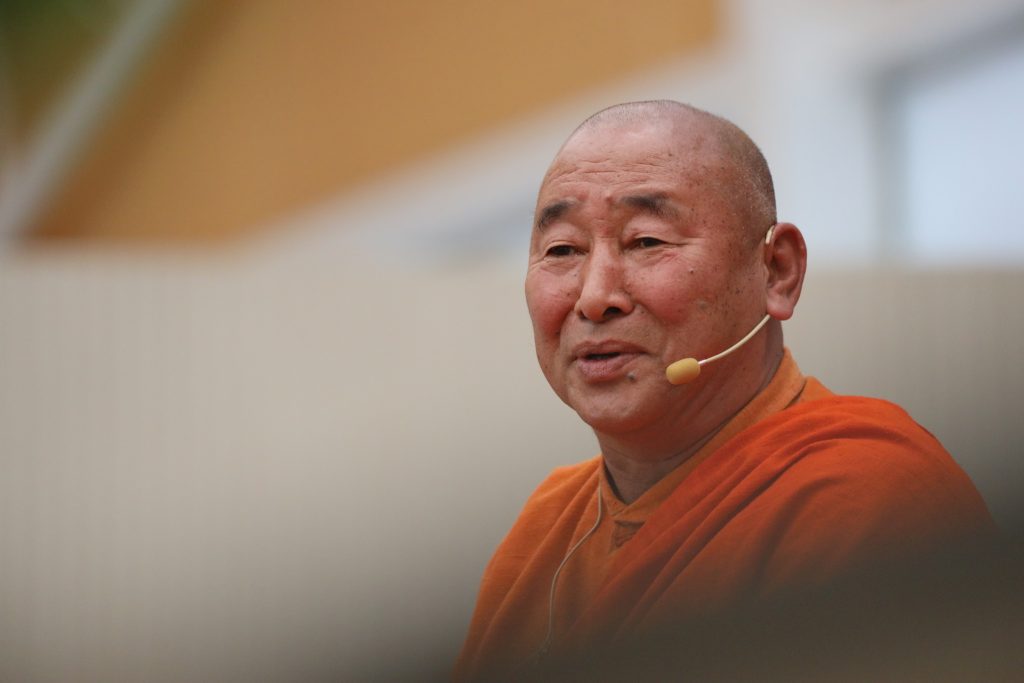

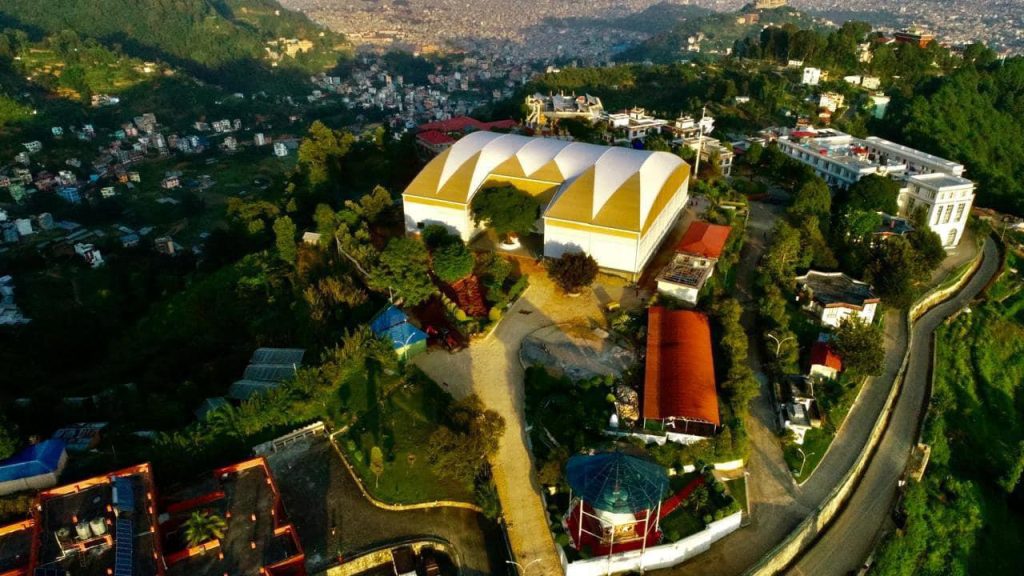

The most Venerable Buddhist Masters, Lams and Eminent Rinpoches from all Buddhist traditions and all over the world are gathered in Bhutan, to hold a profound prayer for Global Peace. For Bhutanese, who are a deeply devout people, this is a time of great significance.

For the people of Bhutan, His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck is the most beloved of all. He is our pride, our hero, and our inspiration. Therefore, we are immensely grateful to all the Venerable Masters and Rinpoches for their presence here at this deeply significant occasion. They continue to play vital roles in upholding and spreading the Dharma across the world. We extend our deepest appreciation and prayers, and reaffirm Bhutan’s commitment to supporting their noble work.

At a time of global turmoil, it is indeed gratifying that Bhutan is able to hold such an important prayer for Global Peace, which will be followed by the Kalachakra initiation led by the Je Khenpo in the coming days.

In the past week, Bhutanese once again demonstrated the exceptional unity and harmony that defines our country. The government, Desuups, Gyalsups, clergy, armed forces, and numerous volunteers came together to work tirelessly and went above and beyond duty to ensure that the prayers were a success. The loyalty and devotion of our people for the country and one another makes Bhutan a true Baeyul.

Our nation of Pelden Drukpa is known throughout the world as a special and blessed land – a place of spirituality, peace, and harmony. The soul of this extraordinary nation is embodied in our people, whose values and virtues – integrity, loyalty, trust, and a deep sense of responsibility – are considered worthy of emulation.

These noble qualities inherent in our people and nation did not emerge by chance. They are the fruits of the blessings of the Triple Gem, the accumulated prayers of our forefathers, and the tireless hard work of past generations who built and safeguarded this precious nation.

His Majesty Fourth Druk Gyalpo’s reign made extraordinary contribution to strengthening our nation.

Sometimes I wonder what Bhutan would be without King Jigme Singye Wangchuck. Bhutan would not be what it is today without an extraordinary, visionary King like His Majesty to guide us.

His Majesty was only sixteen in 1972 when he became the King of a small, landlocked, underdeveloped, and vulnerable Kingdom.

Despite these formidable challenges, His Majesty provided a clear and far-sighted vision for the nation, enacted sound laws for the well-being of the people, and pursued pragmatic policies that safeguarded Bhutan’s sovereignty and security. His Majesty laid the firm foundations for a modern nation state by addressing challenges with wisdom and foresight.

His Majesty pioneered the transformative and globally admired philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH). His Majesty strongly believed that the people of Bhutan must be empowered to shoulder the responsibilities of our future. It was to this end that he initiated the drafting of the Constitution and the introduction of Democracy in 2008.

The peaceful, strong, and prosperous nation we enjoy today stands as a direct testament to His Majesty’s unparalleled leadership, selfless service, and profound sacrifice over thirty-four years of reign.

A great statesman, a fearless warrior, and a wise teacher, His Majesty embodies the qualities of Rigsum Gonpo – the fearlessness of Chana Dorji (Vajrapāni), the wisdom of Jampelyang (Mañjuśrī), and the compassion of Chenrezig (Avalokiteśvara). He is a true Dharma King.

It would not be possible to recount all of His Majesty’s extraordinary achievements. Our people know well the legacy of His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck – as a visionary leader and a wise monarch.

But today, I wish to speak as a son of the man I call my beloved father, my Apala.

On this special occasion, I want to share some of the timeless advice my father gave me throughout my growing years, which continue to serve as my compass.

These are the words from a father to a son, and an insight into the kind of person His Majesty is.

1. Serve the Nation and People with Loyalty and Dedication

There is no greater purpose or higher calling than serving our country and people. You must be willing to make every sacrifice and to uphold duty even above your own life.

2. Safeguard and Strengthen Our Sovereignty and Security

We must do everything to protect, enhance, and strengthen our security and sovereignty. Don’t even let a tiny crack appear; leaving small problems neglected can become dangerous one day. Always be vigilant.

3. Uphold the Dharma

The wisdom and teachings of the Buddha, Guru Padmasambhava, and Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal are our most precious guides for the nation’s journey forward. Always serve the Je Khenpo, our Zhung Dratshang, and all our different religious traditions. Our spiritual heritage forms the very fabric of who we are. It is what holds us together and gives us the identity we value. It makes up the soul of our nation.

4. Preserve and Promote National Identity

As a small nation landlocked between two great powers, our strength lies in what makes us distinct; our language, values, etiquette, and culture. Our people, and particularly our youth, are the ultimate custodians of our national identity and must nurture it for future generations.

5. Protect Our Cultural and Natural Heritage

Our dzongs, temples, sacred sites, and landscapes are our treasures. They must be cherished, protected, and passed down with pride. His Majesty always emphasized the preservation of our architecture, biodiversity, and traditions.

6. Foster National Unity

Our greatest strength is unity – in purpose, in values, and in spirit. United as one family, Bhutanese will always triumph over any adversity.

7. Reject Complacency

We must never grow complacent. The comfort of today must not blind us to the challenges of tomorrow. Complacency sets in very quickly. We fall victim to distractions, lose focus, and take things for granted. That is when we neglect our fundamental responsibilities.

8. Strong People Build Strong Nation

For a strong Bhutan, you must have strong people. Education, knowledge, and reading are powerful means to strengthen our people – to expand minds, deepen wisdom, and prepare for the future. My father would always encourage me to read. He said that no matter what problems we may face, someone has already gone through the same and has the experience to share.

Someone has already solved the challenges, and all that wisdom is contained in the pages of a book.

9. Nurture the Young with the Right Values

Our children are the future of Bhutan. Never spoil your children. Teach them good values and discipline. Above all, young children must never take anything for granted. Appreciation is a very good virtue to possess.

10. Uphold Our National Reputation

The reputation of our country is sacrosanct. It must be built, earned, nurtured, and reinforced. Never rely on legacy. During your time, make sure Bhutan is always seen, understood, and respected as a dependable, righteous, truthful, and honest country — one that is, above all, trustworthy.

11. Establish Good System and Laws

For a just and harmonious society, we must have a good system — and, even more importantly, very good laws.

12. Always be Adaptive

Finally, one of the most profound pieces of advice I received from His Majesty was that different times require different solutions. Humans have been competent and resilient because they have evolved and adapted. Take this lesson from nature: if our country is to remain strong, dynamic, and well protected, if our collective vision is to build an even more prosperous Bhutan, we must constantly evolve, adapt, and reinvent ourselves. We must be agile.

These are the enduring words of wisdom from my father that I carry with me every day.

You may wonder what His Majesty thinks about Bhutan today, in a world filled with uncertainty and turmoil. I want to tell you that His Majesty certainly recognizes our vulnerabilities and challenges and is very much concerned. However, my father has told me how proud he is of our people, particularly our youth – their enthusiasm, dynamism, and desire to make a difference. He sees how deeply we care for each other and for our country, and how proud we are to be Bhutanese. He understands that we are willing to do everything to serve, protect, and build Bhutan. He is confident in our people’s capabilities, and believes that Bhutan has a very bright future.

A King of Destiny was born in Dechencholing Palace in 1955. He built a stronger Bhutan, and his vision shaped the future of our nation. Just as a tree multiplies to become a forest, we have inherited the responsibilities and values of His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the Father of the Nation.

On this very special occasion we would like to re-pledge our loyalty, devotion, and service to the nation. We want to assure King Jigme Singye Wangchuck that we will do him proud, and honour his legacy.

We will make sure that the teachings of Ugyen Guru Rinpoche and Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyel will continue to flourish, and that Bhutan will always remain a special country.

It is an auspicious tendrel that His Majesty’s 70th Birth Anniversary coincides with Lhabab Duechen. The next time these two dates coincide will be on His Majesty’s 100th Birth Anniversary.

May we be blessed to celebrate that day with the same pride, reverence, and happiness.

Tashi Delek.

Source: His Majesty King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck‘s Facebook page